Almost nothing at all is known about the nature of Harmony.

The various systems of Harmony which music theorists have constructed, from the Ars Noveau of the Middle ages to the modern Neo-Reimannian theories, are little more than shallow classification systems. Harmony categorized into modes, Harmony categorized into Reimannian functions, Harmony categorized into Lewinian transformations - all of this splitting up and labeling tells us close to nothing about the underlying nature of harmony; it only succeeds in breaking down and formalizing the styles of the greatest composers into teachable forms. These systems are not so much meant to help us understand Harmony as they are meant to help us wield it. They are not meant to be truthful, but practical.

So, while music theorists have done much work to assert their various systems of Harmony, they have failed in virtually all the areas that actually matter. They have not only failed to address any profound concerns about the nature of music, but also to address even the most basic problems of the field, the most glaring of these being the problem of "Consonance and Dissonance."

It is almost universally agreed upon among Western musicians that there is some harmonic quality called Consonance and an opposing quality called Dissonance; and yet, there seems to be almost no useful discussion regarding the deeper nature of these two qualities. Despite the great attention we have given this subject and despite the many advancements in acoustical science over the past century, we are no closer now to a clear understanding of the phenomenon of Consonance than we were in the Middle Ages. This should tell us that the problem lies not in our sum of knowledge, but in our underlying premises...

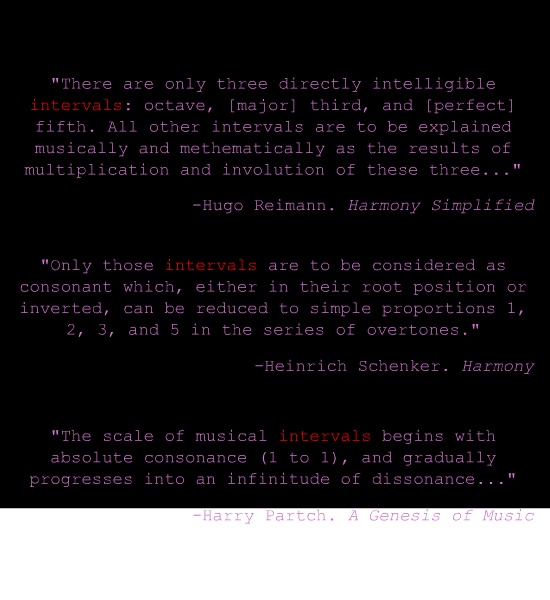

Music theory is currently dominated by a conception of Harmony which originates in the Pythagoreans, and which can be summarized as follows: "An interval is more consonant the more numerically simple it is."

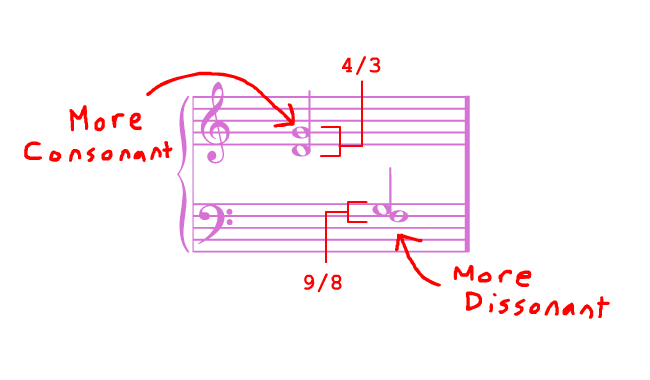

In music, an "interval" describes the relationship between two pitches, usually in the form of a ratio. A pitch at 400 Hz and a pitch at 300 Hz, for instance, create the interval of 4/3. A pitch at 900 Hz and a pitch at 800 Hz create the interval of 9/8. According to the Pythagorean conception of Harmony, the former is more consonant than the latter because the ratio between its two pitches is simpler.

Nothing has been more damaging to the field of music theory than its blind acceptance of Pythagoras' ideas. Basically every single person who studies music theory has internalized his claims so deeply that they cannot even conceive of an alternative.

There are two layers to the Pythagorean theory of Harmony: the superficial equation of consonance with numberical simplicity, but also the deeper, implicit notion that intervals are the source of Consonance. The second idea is the most damaging one, because it quietly redirects all investigations into Consonance towards the interval and away from other possible sources. Under Pythagoras' conception of Harmony, the INTERVAL-RATIO becomes the primary basis of all Consonance-theories.

Read through the Harmonic Treatises of Zarlino, Rameau, Reimann, Schenker, and Partch. In every single one, you will find the exact same method. First he lists off a set of INTERVAL-RATIOS. Only once he has finished appraising each of these intervals as some level of consonant or dissonant does he then feel comfortable using them to reconstruct the classical scales and chords which he is used to. It is so obvious to him that this is the correct order of operations, that the INTERVAL must come first and everything else second.

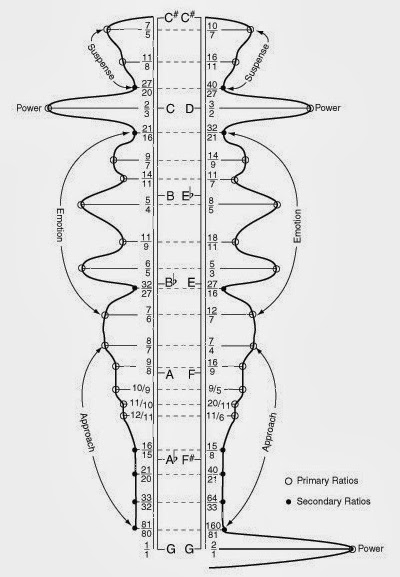

Our preoccupation with intervals has only become stronger in the modern strains of theory. With the old European traditions and systems torn away, the modern theorist has to lean further into the core of the Pythagorean doctrine, which is all he has left to stand on. This is why Harry Partch, supposedly a revolutionary theorist, merely restates the 2500-year-old Pythagorean conception. Partch rebels against the "outdated" Western doctrines of Harmony, only to hold up far older Greek doctrines in their place. Consequentially, Partch's magnum opus begins with a section entitled "Thinking In Ratios" and ends with the "One Footed Bride," his mapping of Consonance onto a range of intervals.

Meanwhile, the field of "psychoacoustics" (music theory with an air of scientific method) holds up the Plompt-Levelt curve as a grand breakthrough. But this is, once again, a mapping of Consonance onto intervals.

In every one of these Harmonic systems the interval is assumed to be the source of Consonance. To music theorists, it is never the harmonic-structure ITSELF which is viewed as Consonant, but rather the intervals which it consists of. A major triad is not consonant; the 5/4 and the 6/5 within it are. The harmonic series is not consonant; just the intervals within it. According to all of our music theorists, Harmony essentially only takes place at the level of the interval, and the broader harmonic structures we have built - the chords, the scales, the songs - are merely sets of intervals shoved together.

Has it occured to no one just how narrow this conception of Harmony is? Has anyone ever questioned Pythagoras? Has anyone ever asked if there really is such a thing as a "consonant interval?" What if it is not the interval, as such, which is consonant, but only the broader harmonic structure which it is a part of? What if every interval is only comprehensible as a fragment of a larger harmonic body? Such alternatives to the Pythagorean conception absolutely must be considered.

Music theory, as a whole, needs to severely broaden its vision. It doesn't matter how widely our conclusions about Consonance vary when they are always restricted from the very outset by bad assumptions which were made 2500 years ago.

Of course, it's always easy to tear down first principles, and absurdly difficult to build up new ones. So where does this leave us?

"If you're going through hell, keep going." So maybe it would be best to keep drilling into Pythagorean Harmony. By understanding precisely what it is, we will begin to understand precisely what it lacks. And here we will find the fertile ground upon which to begin growing a new theory: in the places where the Pythagorean weeds can't invade.

First, it needs to be understood that Pythagoras' music theory was nothing more than an extension of his own philosophy: "the essence of all things is number." Intervals are ratios, and ratios are numbers. In Pythagoras' purely intervallic music theory, number becomes the sole basis of Harmony. Music, as a whole, becomes reframed as an actualization of the principles and laws of mathematics through the vehicle of sound. This is the conception of music which Pythagoras has passed down to us: "music is math." Even now, the idea that "music is math" is widely accepted among musicians, musicologists, and theorists alike. Even the most rebellious and individualistic philsophers submit to the ancient authority when the topic of music comes up: "music is math." Like every truly great philosopher, Pythagoras' innermost desire was not to understand the world, but to enslave it to his own philosophy. Philosophers are conquerers, and nowhere in the entire history of philosophy do we find a greater conquest than in Pythagoras' complete subjugation of music to his own philosophy.

The consequences of this hyper-numerical conception of music are depressing to say the least. Nowadays, the sentiment "music is math" is widely shared among musicians, musicologists, and theorists alike. Music conceived of in this way takes on a cold, abstract character. It almost seems as if it exists in another realm apart from our own, deprived of all flesh and blood, of all earthiness. Whereas other artforms like theatre, dance, and painting are viewed as sensuous, orgiastic, and intertwined with life itself, music seems to always be thought of as cold, logical, and abstract, like the numbers which supposedly form its essence.

Of all the arts, only music has been subject to this autistic, hyper-numerical treatment. Is there anyone who would actually suggest that, when looking at a beautiful painting, we are just perceiving some mathematically perfect object, some function rendered into visual image? The qualities which define a painted masterpiece - its colors, lighting, space, depth, framing, etc. - are all qualities particular to our sense of sight. Any reduction of such qualities to number would be totally pedantic. One could measure out some set of lengths in this painting, and one could argue that their "simple proportion" contributes to the piece's beauty, but only an absolute fool would claim that the entirety of the piece's aesthetic value rests on these proportions. But this is the exact treatment we have given music!

Compare the language of music theory with the language with which we describe other sensory phenomena. Our language for describing smells and tastes is almost entirely based on analogy: "fruity," "nutty," "earthy," "salty," "spicy," - every one of these descriptors invokes an association with some actual sensual experience. Sight is described almost entirely in terms of color and lighting, qualities which are specific to that particular sense-world, qualities not bound by number. Even our words for colors are etymologically rooted in sensory experiences. Green shares a Proto-Indo-European root with "grass" and "growth", yellow with "glow" and "gold," red with "reed" and "ruby." From this, it seems clear to me that each color-word originated as a reference to an actual visual experience (i.e. green, red, and yellow begin as grass-like, ruby-like, and gold-like). Our language for describing Harmony lacks entirely this kind of straightforward connection to the senses. Words such as "voice-like," "buzz-like," "howl-like," "chirp-like," "scream-like," "whisper-like," and "hum-like" are entirely absent from music theory, even though they would probably reveal far more about the meaning of a given harmony than the conventional "this chord consists of a 5/4, 5/3, 4/3, and 2/1."

Here, we seem to have found precisely what music theory lacks: a connection to our basic acoustical experiences, a connection to SOUNDS. Harmonies are sounds, but they are rarely talked about that way. The basic sounds which make up our general acoustical experience have been ignored in favor of fanciful ideas about number-magic. Without this firm root in the sensory world of sound, music theory floats high above in a cloud of abstraction. "Harmony is number." So what? Do we really think that by saying this, we somehow understand music better than we did before? what does it really tell us about Harmony, other than the fact that it is measurable?

In this blog, our goal will be to develop a theory of Consonance which has its basis, not in numbers, but in actual sounds. We take music for what it is: an artform thoroughly rooted in our sense of sound and which cannot be understood outside of that particular sense-world. We reject the Pythagorean conception of Harmony which, by its reduction of Harmony to a purely numerical form, has given birth to music theories which are hyper-logical, sterile, and lifeless. Every numerical representation of Harmony, therefore, will be treated with the utmost suspicion, and every attempt will be made to understand Harmony by drawing analogies to actual sounds. The animal call, the crashing waves, the hushing wind, the crying cicadas - these basic acoustical experiences form a far greater basis for a harmonic system than do ratios and formulae. It is upon this basis that we will strive to create a harmonic system which is as fiery, strange, and poetic as music itself, a music theory which dances along to the music which it interprets.

We begin with a simple maxim: all sound is made up of frequencies, oscillations of air pressure over time. Frequencies should be regarded as atomistic to the world of sound, in that they are the indivisible sound particles which by themselves mean little but out of which every sound can be produced. On the other hand, to say that the sound-world is “just a bunch of frequencies” would be a reduction as shallow and useless as the reddit-materialist motto: “we are just a bunch of atoms.”

Clearly, what matters is not the frequency-atoms themselves, but the shapes which are made when they combine together; and from this infinite set of shapes, I distinguish between two fundamental types: Tone and Noise.

A tone is a sound which is made of many frequencies but is only heard as one pitch. Noise is a sound which is composed of many frequencies but is heard without pitch.

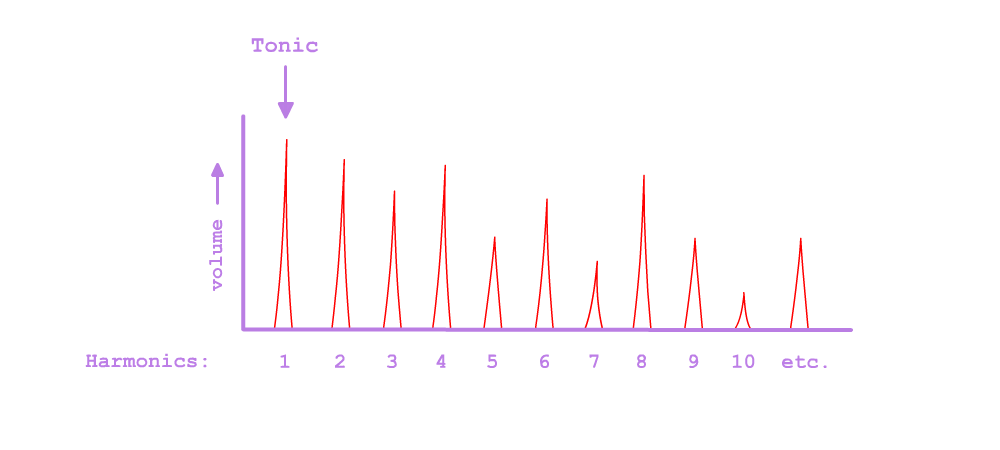

This is the frequency spectrum of the sound produced when a C3-note on a piano is played:

This is a tone. We have multiple frequencies playing simultaneously, but rather than hearing many pitches, as one might expect, we only hear one. Every tone that we hear, whether its source is a piano, violin, human-voice, didgeridoo, bird-call, or trumpet, is, like the tone above, collection of frequencies which combine together to create a single pitch. This is a fact which often suprises the uninitiated into acoustics, because the pitch created by the set of frequencies is so absolute and so pure.

This is the frequency spectrum of the sound produced by a cymbal crash:

This is a noise. Once again, we have multiple frequencies playing simultaneously, but this time we do not perceive any single pitch; rather, we perceive a general range of pitchless sound.

So, we have two fundamental types of sound: sound-with-pitch and sound-without-pitch, Tone and Noise. Oftentimes, the words "frequency" and "pitch" are used near-interchangeably, but here we have a clear distinction between the two: frequencies are the physical components of sound, but pitch is a feeling. To use a geometrical analogy, pitch can be regarded as much like an acoustical center which defines the corrdinates of a group of frequencies.

The disparity between a sound's actual set of frequencies and its perceived pitch-center is epitomized in the two sounds, Tone and Noise. In this blog, I will argue that much of our sense of Harmony results from this disparity.

Noise is the lowest and most rudimentary state of sound: a disparate mass of frequencies unbound without pitch, without center.

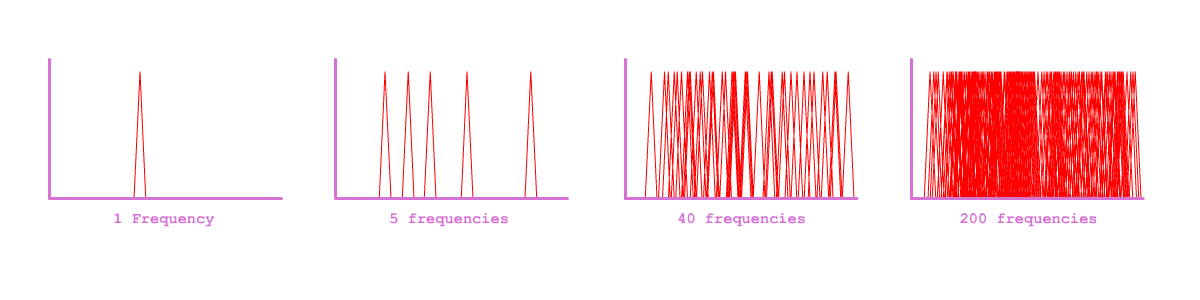

Taking for granted that a frequency is a particle in acoustical space, "noisiness" can be described as a large accumulation of these particles such that they begin to clutter our range of hearing.

A collection of frequencies becomes a true noise whenever it reaches a certain level of density, and no individual pitches can be recognized within it. Just as we would perceive thousands of grains of sand not individually but as a single homogenous substance, so too do we experience thousands of frequencies not individually but as a single homogeneous noise. A noise is merely a mass of sound, an amalgam of various frequency-particles which appear to us as a single sound only because of their proximity.

Whereas an acoustical structure (a harmony) is characterized by the placement of its frequencies, a noise is only characterized by their density and the range which they occupy:

"Brown" noise (frequencies occupying the lower range of human hearing):

"White" noise (frequencies occupying the full range of human hearing):

"Purple" noise (frequencies occupying the higher range of human hearing):

This is the difference between an acoustical structure and an acoustical mass: noises lack any sharp edges; they are homogenous fields of sound which spread out evenly across our acoustical experience. They go unnoticed because they are always floating there in the peripherals of sound.

As a rule, many frequencies will obscure each other, leading to Noise. The Tone represents the singular exception to this rule: its' frequencies compound together into a single pitch.

Every Tone comes in the form of a Harmonic Series. The Harmonic Series, sometimes called the "overtone series," is a series of frequencies naturally created by the resonations of a physical body. If a piano-string, for instance, begins to vibrate at a certain frequency, that frequency will not only travel through the air but through the rest of the piano, reverberating through its body and its other strings. By these reverberations, a series of resonant frequencies, or harmonics is produced. These harmonics will all be multiples of the initial frequency, or the tonic. If the tonic is 100 Hz, for instance, a series of harmonics will be produced at 200 Hz, 300 Hz, 400 Hz, 500 Hz, and so on.

Every tone that we hear contains this series of harmonics. Every trumpet-call, guitar-note, bird-song, animal-call, and human voice conceals, within itself, the same imperceptible frequency-structure.

In order to begin to understand the nature of structure within the acoustical world, the reader needs to first understand how radically different a frequency and a tone are from each other. The difference between the two is constantly undermined in music theory, where every tone is reduced to a note - that is, a "pitch-class." To music theorists, the pitch of the note we are hearing is all that is worthy of discussion. Whether that pitch comes in the form of an infinitesimally small frequency-dot or a tone with its fully-fleshed out body of harmonics is treated as completely arbitrary. But this is a horrible mistake. We only have to listen to these two sounds, frequency and Tone, side-by-side to recognize how far apart they are acoustically.

This is a single frequency in isolation:

But THIS is a tone:

Both are heard as a single pitch, but the latter has a BODY; it has DEPTH! While the frequency is just an acoustical "atom," the Tone is an elaborate acoustical molecule, one in which many interrelated harmonics contribute to a single over-arching feeling of sound.

We need to take care not to conflate music-as-it-is-written with music-as-it-is-heard. On sheet music, every tone is reduced to its pitch. But an actual tone, one played into existence, is far more than just a pitch-class; it is a robust acoustical structure. The Tone is, itself, a harmony.

The Tone is an anti-Noise. Whereas a noise is a haphazard grouping of disparate frequency-particles, the tone is a body which meaningfully incorporates these particles into its structure. Every frequency within a given tone assimilates to one pitch. This pitch is the acoustical glue which simultaneously holds the tone together and defines it against the rest of the acoustical world. Noise is the "default" state of sound because it is natural for separate frequencies to have separate pitches, pitches which necessarily detract from each other. But in the Tone, every harmonic forgoes its own pitch-feeling in order to assimilate into that of the tonic. Rather than a cloud of disparate frequency-particles, we get a single, unified body of sound.

In the Tone's plurality of harmonic identities we witness something entirely different from Noise's grey homogeneity. It is only by their separate places in the Harmonic Series that the harmonics attain distinction from each other. In a noise, every frequency is just one point in a general area, but in a tone each frequency is a special and uniquely defined node in an overarching tonal structure. Each has a particular role in fleshing out the sound of the pitch. The 2nd, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 11th, and 15th harmonic, etc. - each of these boasts an entirely unique acoustical feeling; they are, acoustically, as different from each other as red, blue, green, yellow, purple, and orange. The Harmonic Series is, indeed, much like a spectrum of various harmonic-colors. And although these "colors" compound together into the "white light" of the Tone, the absence of any of them has noticable effects on the over-arching tonal feeling. So the Tone is a robust structure, within which we see the first traces of harmonic identity.

Tone and Noise represent the furthest extremes of the range of our harmonic experience. The Tone is one-pitched sound; Noise is sound-without-pitch. 1 and 0, Form and unform, unity and homogeneity, structure and mass. The whole of our acoustical experience rests upon the distinction between these two extremes.

To truly appreciate how fundamental Tone and Noise are within our acoustical universe, one has to actually go outside, away from the intrusion of public speakers, and to take note of the sounds which reach the ear. One will soon find that all of these sounds can be neatly categorized into either a tone or a noise. The crashing of ocean waves, the cry of cicadas, the rolling of tires along the highway, the roar of planes - these are all noises, vague blurs of pitchless sound. The singing bird, the idle conversations, the animal call, the car horn - each of these is a tone, a single fluctuating pitch buffered by a harmonic series.

There is no silence in our world. Every moment of our acoustical experience is marked by a background noise. Air conditioning, crying cicadas, rustling leaves, wind - each one of these contributes to a constant, inescapable undercurrent of pitchless sound. The world of sound, at its lowest level, is a boundless landscape of noises. Tones, by comparison, are fleeting and rare. They appear briefly among the vast noise-scape flashing their brilliant spectrum of harmonic-colors before dissapearing back into the Noise-mass. Each tone is a brief spark of light, a flickering star which draws the ear from the overwhelming acoustical darkness of Noise.-->

Everywhere we look, therefore, we find the same image of the World of Sound: a timeless landscape of noises upon which many tones bloom and whither. THIS is the world of sound in its purest, most untouched state, before background music was inserted into every public space. This is the acoustical environment within which our ear developed and according to which it transformed itself. There were no intervals, no perfect-fourths, no perfect-fifths, no major triads; only Tone and Noise poised against each other like figure and landscape.

Human speech consists of a quick fluctuation between various Tone-timbres and Noise-ranges. Vowel-sounds, such as "Ah," "Eh," "Ee," "Oo" and "Oh", are all tonal sounds which we distinguish according to their different timbres. Sounds like "Ch" "Ss" "Tuh" and "Puh" are all noises which we distinguish according to their different ranges. In speech, therefore, we witness a prototype of Harmonic progression, a sequential ordering of the two basic sound-types, and a pushing of each one to the expressive limits allowed by the human voice.

The dichotomy between Tone and Noise is as as fundamental to the ear as that between Light and Dark is to the eye, and equally rife with spiritual meaning. Our ear is not, as theorists are so eager to believe, a cold and mechanical interval-calculator; our ear simply recognizes the basic sound-forms that it evolved alongside. It does not measure out;it recollects.

My answer to the Consonance problem takes the form of a simple analogy: Consonance is Tonality and Dissonance is Noisiness..

The Tone is the only pure Consonance. Every sound is a collection of frequencies, but only in the Tone do these frequencies interlock so seamlessly that our ear fails to distinguish between them entirely. The Tone is the singular greatest example of absolute acoustical unity, and the epitome of what is meant by the word "harmony": the resolution of many (frequencies) into one (pitch).

Noise, on the other hand, is a pure Dissonance. Noise is a screeching mass of conflicting sounds. It is the result of so many disparate sounds piling over each that all distinctions between them are blurred, leaving only a grey, pitchless sound-mass.

"Consonant and Dissonant" means "Tone-like and Noise-like." Every consonance invokes a feeling of acoustical wholeness, pitch-center, and structure; every dissonance invokes a feeling of acoustical disparity, pitchlessness, and homogeneity. All Harmony operates in the liminal space between these two extreme sound-feelings.

The moment we begin to view harmonies, not as groups of notes bound together interval-by-interval, but as actual SOUNDS, it becomes clear how certain harmonies are more "Tone-like" than others. For instance, a tone at the pitch of C1 and an octave spanning from C1 to C2 are nearly identical!

Here is a C1-tone:

And here is a C1-tone and a C2-tone played simultaneously:

If we are not already accustomed to the sound of an instrument, then an octave basically sounds indistinguishable from a single note. THAT is Consonance. THAT is what it means for a sound to be Tone-like. It means that, although a "single tone" and an "octave" are easily distinguishable on paper, in terms of ACTUAL SOUND, the distinction between the two is arbitrary.

All consonant harmonies, like the octave, are groups of tones which fit together in such a way that they create the impression of a singular tone. Many tones can be "Tone-like" in combination.

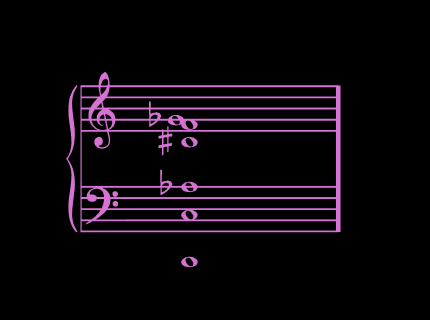

Say that a church-organist is having an off-day, and he accidentally starts the hymn by playing this chord:

The chord consists of 6 separate tones - 6 ENTIRELY DIFFERENT PITCHES which, in their fight for the ear's attention, end up obscuring each other. The chord, therefore, is a quasi-noise. A dissonance.

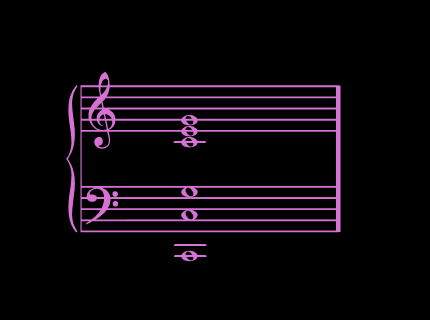

So, quickly fixing his mistake, the organist voice-leads to a strong consonance, a towering C-major chord:

Just by slightly shifting each of these pitches, the organist has eliminated that unsettling feeling of 6 pitches fighting against each other. But why? Why do these 6 tones feel unified whereas the previous 6 tones do not? It is because, although the organist is technically still playing 6 tones, all of these tones conform to a single Harmonic Series!

When multiple tones fall along a single Harmonic Series the resulting sound tricks the ear. Our ear recognizes not the individual tones but the over-arching Series which they fall into. As a consequence, rather than hearing 6 separate tones, we perceive a single Tone-like sound! A consonance!

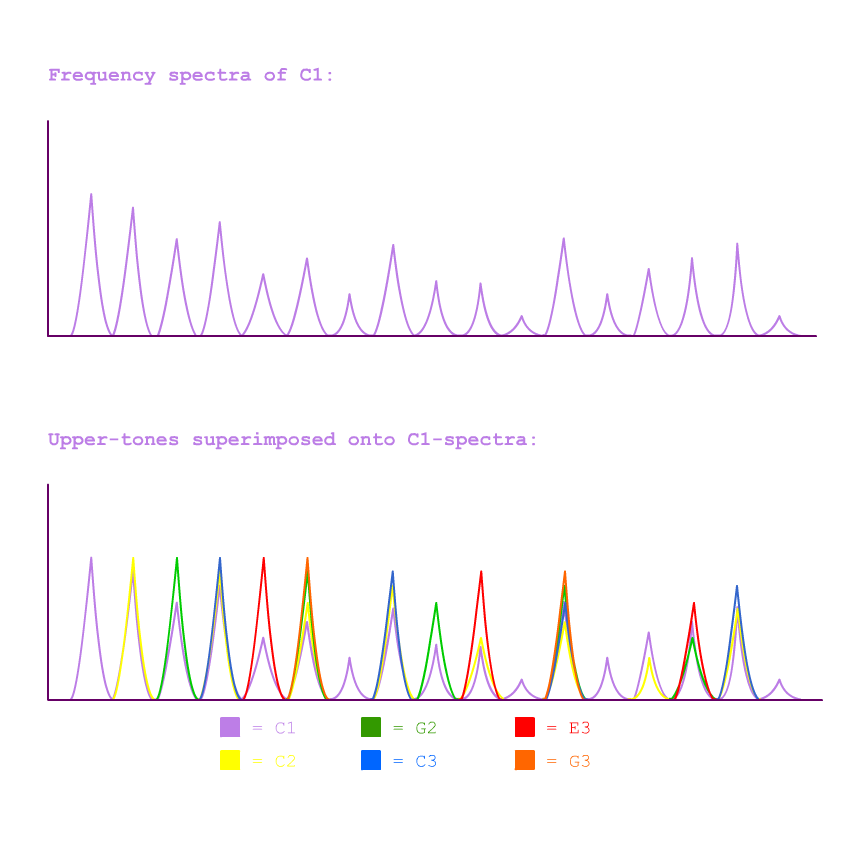

In the consonant chord, the pitches of the 5 upper-tones are each incorporated into the harmonic series of C1, thereby, assimilating into its pitch-feeling. The tonic of the C2-tone is the same as the 2nd harmonic of the C1-tone. C2, therefore, is heard as an extension of C1's 2nd harmonic. G2, likewise, extends from the 3rd harmonic; C3 from the 4th; E3 from the 5th; and G3 from the 6th. What we get, as a result, is a single network of frequencies stemming from the pitch of C1.

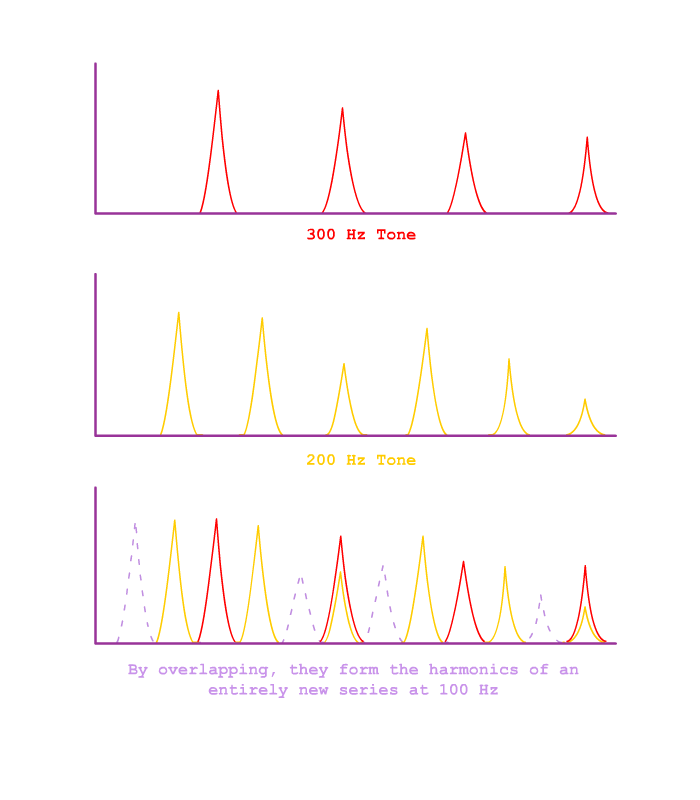

The most widely accepted psychoacoustical explanation for Consonance is Helmholtz's theory that Consonance is the direct result of overlapping harmonics. But this is only a half-explanation. It doesn't get to the core of what's really happening. What Helmholtz misses is the fact that whenever 2 separate harmonic series overlap with each other, they necessarily create a larger kind of meta series through their union:

It is by virtue of this "meta" series that the tones unify. The source of consonance is not in the two actual tones (the interval), but in the overarching Tone-like sound which is created by their union. They literally become one tone!

So, Consonance is not a matter of number, but of semblance. A sound may not be a pure tone, but it might be similar enough to a tone to at least rouse our Tone-seeking ear - to make it turn its head and go "huh? wuh?".

Tonality, then, is not something peculiar to Western Harmony, but a principle which is common to all styles of Harmony. Wherever one finds a Tradition of Harmony, whether it is Islamo-Indian Raga, American Jazz, or any of the thousands of locally-bound folk musics lying scattered across the globe, one will always find some elaboration upon the Tone. All sound-structure is Tonal, and the properties inherent to this structure are something which every composer must deal with, just as every architect must deal with the laws of gravity. This is a fact not consciously realized but instinctually felt by every composer, every tuner, and every performing musician. Everyone who has ever contributed to the progression of their own musical culture has, without realizing it, felt the pull of the Tone upon his ear. The sense for Tone-like sound, hammered into his psyche by millions of years of evolution, unconsiously influences every musical decision he makes, driving him to create scales, chords, progression, melodies, and songs which ground themselves in the firm structure of the Tone. The moment that he strays too greatly from this structure, he invokes Noise, and, with it, the grey and banal feeling of acoustical homogeneity.