"pls dont making fun of me"

"pls dont making fun of me"

It is generally agreed upon, among Western Musicians, that there is something called Consonance, and a negative to that which we call Dissonance; yet, there is almost no useful discussion regarding their underlying nature.

We are apparently satisfied with leaning back into the ancient Pythagorean saying, "Consonance comes from simple-number ratios." Pythagoras, as the first Western thinker to analyze Harmony, was able to take control of Music Theory in its fetal stages. He was in the privileged position to decide its initial trajectory, and to transform it in such a way that its early stages of development would be necessarily PYTHAGOREAN. His presumptions about the nature of music, therefore, became the unquestionable axioms still which dominate the psyche of the modern "music theorist," such that he will happily and stupidly repeat "Music is the language of numbers."

Pythagoras famously demonstrated that the sounds produced by string lengths at ratios of 1/2, 2/3, and 3/4, blended together nicely, concluding thusly that these were the most harmonious intervals and that they were harmonious precisely because of the simplicity of their ratios. The musicians of Pythagoras' era went into heat over these ideas. They drooled over the thought of a mathematical basis to Harmony – something rigid and logical, which could trap Harmony in its steel-embrace. And with Harmony ensnared, the musical world could dissect it, pulling off its wings, “reasoning out” its beauty. These musicians, in a sadistic frenzy, began reverse-engineering the musical scales of every culture, autistically reducing them into sets of ratios. “Ah yes,” the theorist says; “THIS scale is composed of the ratios: 9/8, 5/4, 3/2, 5/3, and 2/1,” and he smiles as if he has just overcome all of the mysteries of nature.

From the very beginning, Pythagoras takes for granted that there even is such a thing as a "harmonious interval" - that we are able to take two pitches and say "These are consonant to each other! end of story!" - and everyone just seems to accept this. For the 2 millenia after Pythagoras, nobody would question whether it was the interval-ratios themselves which we found consonant or something even deeper. No one would question what authority Pythagoras had to wed music to mathematics, nor what he had to gain from this arranged marriage. Pythagoras, after all, wasn’t a musician. He spent his afternoons with a monochord, painstakingly assessing one interval after the next, comparing their sonorities before proclaiming “the 3/2 ratio is really cool I think!!” And so, the study of music theory ironically begins with the most UNMUSICAL experiment - one which ignores things like Tonicism, Timbre, Gravity, and the human hearing-range.

Pythagoras was an incredible philosopher, but we must not forget the basis of his world-view: “Number is the essence of all things!” His is a philosophy of NUMBER, not a philosophy of Harmony. If we base our conception of Harmony strictly on ratio, we are confusing the beauty of music for the beauty of math, and the end result of this is a music theory which is inhumanly cold and sterile, rather than one which dances to the music it examines.

One of the most fantastic developments in Harmony-as-science happened in the Late Middle Ages when Marin Mersenne, a French monk, discovered the existence of OVERTONES and theorized their direct relationship to consonance. The intuition is easy to follow here: tones which are consonant with each other have this tendency to BLEND together. The most pure consonances happen when tones "hug" each other, interlocking into a seamless concord. Mersenne discovered that within each Tone, that same phenomenon of “blending” was occurring at a microcosmic level. All this time, these “overtones” were hiding underneath all of harmony, their consonances so pure that they evaded our ears all-together! At last, there was an example of consonance in nature! Finally, we had a schematic for Harmony which was not drawn up by the clumsy hands of men. It was by this incredibly original discovery that Mersenne unknowingly started a school of Harmony completely separate from the ratio-brained Pythagoreans – A school which ascribes Consonance to THE SERIES OF OVERTONES.

Not only should The Mersennian Conception of Harmony have been recognized as an astounding breakthrough in music, but also as the opportunity for a clean break from the Pythagorean train of thought; yet, his forerunners have spent the last half-a-century meekly fumbling around with his ideas. Any musician who seeks a follow-through on Mersenne's ideas will more-or-less find a collection of Harmonic Treatises written by German composers. Rameau, Reimann, Schenker, Hindemith - the area of Harmonic Theory was, during the Classical Era, completely dominated by Germans. To say that these men failed ot build upon the Mersennian Conception would be an understatement; in truth, they regressed from him! Mersenne, upon discovering the Overtone Series, immediately realized its implications regarding Consonance: that if the first 6 Overtones are super Consonant, than the 7th should be somewhat Consonant as well. Contrast this with the views of Reimann and Schenker:

In the German treatises, you'll find a lot of explanations like this: "Because this doesn't work with our tonal system..." "For the sake of our art..." "... Our ear rejects this." You see, these guys wanted nothing more than to explain the BRILLIANCE of the European Style - to justify the beauty of THEIR music, rather than music as a whole. To fulfill this end, they were willing to hold up the Overtone Series and shout "Here is nature! And nature justifies our music!", but if something appeared in the Series which did not SEEM to exist in German Music (like the Consonant 7th Overtone), they would suddenly shrug their shoulders: "hmmph. Art justifies itself." This absurd double-standard betrays the German School's short-sightedness, its inability to look beyond its own Harmonic Style, and its mind-numbing fear of taking the Overtone Series to its logical conclusions. So incomplete is their delineation of the Overtone Series, that they had to fill in its logical gaps with weak, unintuitive ideas, such as Reimann's infamous theory of "Undertones" - that mind-virus that has now spread to the disciples of Jacob Collier. So, the same masturbatory sense of Nationalism which fueled the Germans to write Harmonic Treatises in the first place, also led them to a lack of objectivity which corrupted their Music Theory from the inside. In the end, the Harmonic Treatises of Rameau, Reimann, and Shenker only work as instructional textbooks for 17th-Century chorale-writing. They are fundamentally worthless to anyone trying to understand the divine principles of Harmony.

In all of this time, it seems to me that everyone has overlooked a rather obvious idea – a simple expansion upon the Mersennian conception: a single Tone, despite being composed of multiple frequencies, is heard as ONE SINGLE ACOUSTIC ELEMENT. Consonance represents the tendency of sounds to blend together, and this "blending" reaches its zenith in the single Tone, in the seamless interlock between its Overtones. My conclusion, therefore, is that the Tone EMBODIES Consonance. Heard alone, the Tone requires neither elaboration nor resolution. It is in perfect harmony with itself. The Tone is the epitome of unified sound, and the only PURE CONSONANCE.

My thesis is simple, and 3-part:

1. The single Tone embodies Consonance

2. A sound is only Consonant in as far as it resembles the Tone.

3. Tonality is the elaboration upon the single Tone over time.

You will notice that, over the course of this blog, I avoid referring to any interval as "consonant." My friends, we must avoid the term “consonant interval” at all costs. It is a snake leading us down into the Pythagorean grass. I think that, after 2500 years, it is finally okay for us to step away from this grass and break free of the cold, mathematical axioms which have dominated Western Music Theory. There are no Consonant intervals! There are only harmonies which imitate the Tone (Consonance) and everything else (Dissonance)!

The world of sound is composed of frequencies - fluctuations of air pressure. Frequencies as I am describing them should be thought of as the atoms of the Acoustic Universe. They are the basic acoustical particles which can be arranged into every possible sound.

Before understanding the higher forms that sound can take, it is important to understand sound at its most rudimentary: Noise. Noise is the default state of sound. It occurs when frequencies group so closely in pitch that they become indistinguishable from each other, blurring together into a shapeless, homogenized soup. Within this frequency-soup, separate pitches are obliterated, crushed so tightly together that they become assimilated into one another. Every frequency within noise is of equal value and, thusly, deprived of identity, making noise a pitch-obscuring darkness. Accordingly, noise has this feeling of emptiness to it; it is substanceless - devoid of both value and identity, and lacking the divine spark of PITCH which gives sound life. Noise feels like an acoustical void; it is sound at its most raw.

When I say that noise is the default state of sound, I mean that its formlessness is an overwhelming constant. Noise is underneath and behind and all around everything we hear; it eternally occupies the background of the acoustical world. Noise is like the "waters of chaos" which are talked about in every creation myth, in that it is both the negation of form, and simultaneously the precondition for form to exist at all. All organized sound is pulled out from the these waters, given form precisely because of its self-importance - its transendence beyond flat, grey equalization.

The default state of frequencies (and thusly the default state of sound) is NOISE. Noise is a group of frequencies which are so close in pitch that they become indistinguishable from one another. They blur together into this shapeless frequency-soup where all sound is completely equalized. In such a soup, there is no room for identity. The frequencies within in noise crush together so tightly that any pitch is obliterated. Noise, therefore, is the pitch-eater. It is acoustical chaos.

Often, we think we are sitting in silence when we are actually ignoring the constancy of noise. This is because “silence” describes a lack of acoustical substance. Fundamentally, “silence” is synonymous with “noise” because they both describe the backdrop of the acoustical world – a backdrop we are naturally indifferent towards. Noise is a body of water we have floated in long enough to become completely unaware of. Ripples of sound often dance across its surface, but these often sink back into obscurity before they can even be recognized. Despite its sheer volume of frequencies, noise does not have a “full” sound to it; rather, it imppresses upon us a feeling of emptiness. Noise is a non-thing – an acoustical null.

This acoustical null is the default of sound. It surrounds us constantly: in crowded areas, in the wilderness, in traffic. As I write this, I am listening to the hush of the AC, the faint electric whirring of several household appliances, the cars passing on the nearby highway. Even in my confined little writing-space, noise is ever-present. It lies underneath and around our entire auditory experience.

Frequencies naturally collect into a pitchless mass of sound, but what is the alternative? Does every frequency naturally intrude upon the pitch of every other frequency, or is there some meaninful way to combine them?

Noise is formless and pitchless precisely because every frequency within it is of equal importance; therefore, the exception to noise would have to be some grouping of frequencies in which some frequencies are prioritized at the expense of others. As such, this group of frequencies would take the form of a hierarchy. Rather than being a collection of disparate frequency-particles, it would be a structure which delegates importance of sound. This group of frequencies, my friends, is the TONE.

The structure of the Tone is where harmony begins. Where noise is a soup of aimless frequencies, the Tone is a body with an organizational pattern. Within the Tone, frequencies rank themselves, forming a hierarchy which delegates primary importance to a single pitch. This primary pitch becomes the center around which all of the other frequencies orbit, and within its gravitational pull, the primary pitch unifies the entire group into a single acoustic element - into a molecule with a nucleus. The Tone, therefore, orders sound into a unified structure, elevating it beyond the surrounding frequency-chaos. The Tone is sound given life, pulled out from the primordial-ooze of noise.

Tribal-man lived surrounded by a dark, obscure wilderness which actualized itself acoustically as noise. The rustling of leaves, the cry of cicadas, the blowing of wind – these noises forced man to subconsciously link the utterly inhuman mystery of the outside world with the sound of noise. To man, noise is plant-and-insect-world; it is something raw and primordial and all-consuming.

The Tone, inversely, represents warmth and familiarity. The human-voice is tonal. We are born carrying the Tone within our chests, and at the moment of birth, we invoke it with a loud cry - a proclamation of our entrance into the ancient cult of Tonality. From above, our mother rains down her soft cooes and melodies, her soft tonal blanket which nurtures and warms us. From the very beginning, the Tone is not only WITH US but within MOMMY'S VOICE; the Tone represents sound at its most intimate. As we grow, we find that the Tone is not only the aural signature of Mommy, but of our family and friends, and we look for other places in nature where Mommy's Voice might be hiding. The meowing cat, the whimpering dog, the singing bird - we find that the Tone lies in the voices of our animal brethren. In hollowed-out tree trunks, in conch shells, in the guts of lamb, in the tortoise shell - the Tone hides itself in these husks of life as a ghostly echo of what once inhabited them. As we discover tones hiding throughout nature like little gems, nature becomes more familiar to us. It becomes more human and more LIKE MOMMY.

The difference between Noise and Tone naturally represents the difference between the foreign and familiar. The Tone is a safe-harbor from the primordial chaos of the outside world. That this molecule of sound seems to order the acoustical world around it is a great feat of sound-magic. It's only natural, therefore, that we would fall in love with this sound-magic and draw out as much of its beauty as possible, that we would build massive structures from it, and that we would learn all of the ways to play with it. This sound-magic is, of course, "CONSONANCE," the binding force within all Harmony.

Here we arrive at the core of the Marsennian conception of Harmony: the Harmonic Series of Overtones as a "Consonance-map." This Harmonic Series describes the pattern into which a tonal collection of frequencies is arranged; thus, it is the anatomy of the Tone - the Tone viewed internally. All consonances are reflections of this tonal anatomy; so, by analyzing the Series, we are analyzing the structural qualities of consonance at their most fundamental.

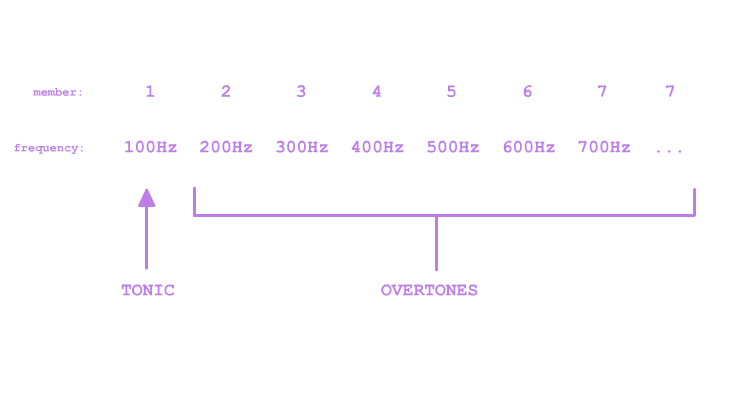

The Harmonic Series is composed of a fundamental frequency which we call THE TONIC and the infinite set of OVERTONES which are multiples of the Tonic. Every member of this series, the Tonic and each of the Overtones, I will refer to as a HARMONIC. All of these Harmonics are equadistant from each other, and their common divisor is the Tonic. If we were to arbitrarily choose 100Hz as our Tonic, its Harmonic Series would look like this:

The frequencies of this Harmonic Series will not be perceived separately; they will appear as a UNIFIED TONE with a single pitch. And this single tone-dominating pitch will be that of the TONIC.

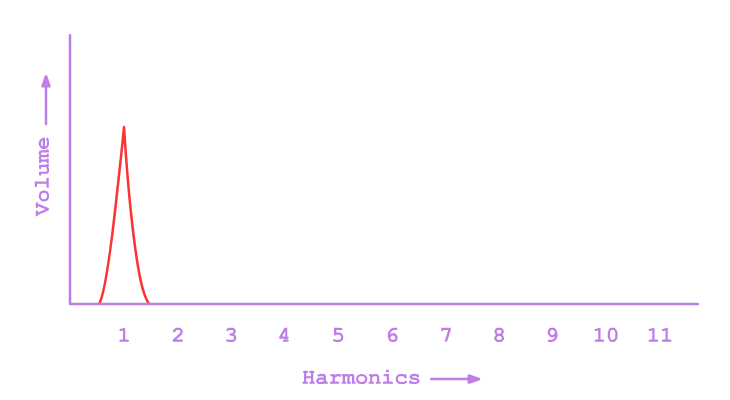

Here is an isolated frequency at 100 Hz:

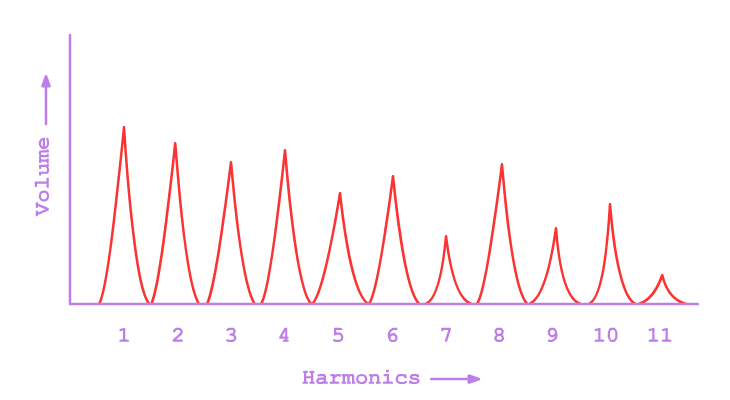

Here is a TONE at 100 Hz with a full range of Overtones:

Notice that the Overtones only ADD to the sound of the 100Hz Tonic. Their pitches are barely noticable if you intensely concentrate on them. They are only audible as extensions of the Tonic's pitch. This is what I mean when I say that the Tone is a HIERARCHAL structure: The Tonic is the dominating force of the Series, and every Overtone sacrifices its own pitch to enhance the volume of the Tonic. As such, the relationship between Tonic and Overtones is like that between king and servant: the latter sacrifices itself to the former and, thereby, gains an identity as its extension. The Tonic is the goal and ideal to which the entire Series dedicates itself. It is the central point which unifies the entire web of Harmonics. If the Tone is a divine temple, then the TONIC is the shrine at its very center - the fountainhead which pours out consonance-magic and channels it through the entire surrounding world.

The relationship between the Tonic and Overtones should illuminate some of the nature of Consonance. Consonance necessarily implies some kind of Tonicism - some pitch which dominates the entirety of the sound. Upon hearing any Consonance, our entire musical experience becomes contextualized. The Tonic becomes an axis mundi from which the entire acoustic universe extends, and one thousand rays of consonance shoot outwards, bouncing off of the infinite Series of Overtones and pushing the darkness of noise into our peripherals. As the Tonal is cleaved apart from the Non-Tonal, our Harmonics Universe achieves form. It is no longer an indiscriminate void of noise; it is a COSMOS with distinction, structure, and gravity.

The Harmonic Series is a conceptual "pitch-map" for a tone's range of Harmonics. That the Tone's harmonics are all multiples of its tonic is the basis of its structural integrity. But when a tone actualizes itself, each of its Harmonics has a VOLUME relative to every other Harmonic. Two actual tones might have identical Harmonic Series, but the distribution of volume among their Harmonics might be completely different, resulting in a complete difference in tonal feeling between the two. This quality of "tonal feeling" is called TIMBRE.

Above are Tones sounded from a piano, guitar, and trombone, respectively. They all have the same Tonic pitch and are thusly composed of identical Harmonic Series, but what varies between them is their Timbre- the distribution of volume among their Harmonics. Timbre is kind of like the flavor of each Tone. All of the Tones heard above are purely consonant, but each of them has a distinct TASTE - a different "color" to it.

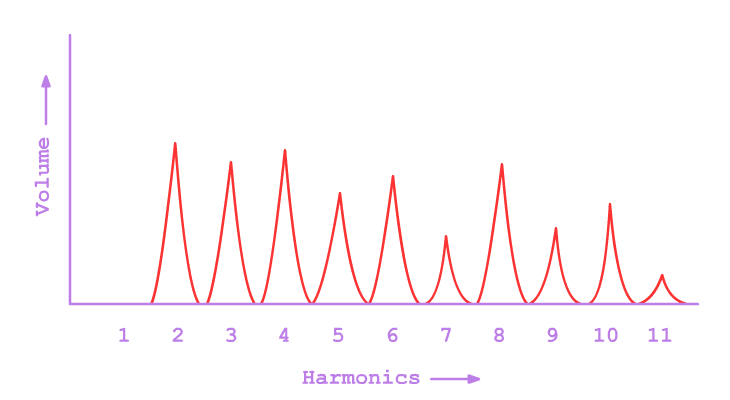

If we graph the harmonic spectra of each one:

Notice that every unique shape the Harmonic Series can take will result in a completely different Timbre. So, while all tones are grounded in an unchanging Harmonic Series, they are still extremely variable. The pure consonance of the Tone can "express" itself in so many different ways depending on its Harmonic "shape."

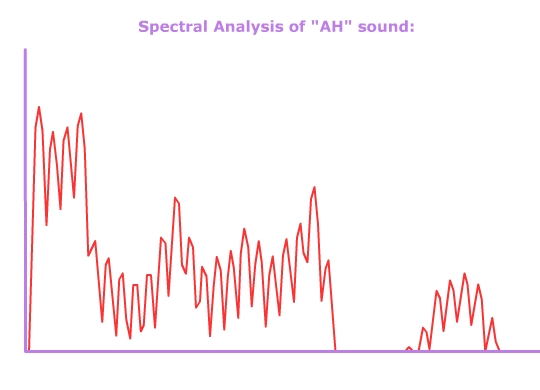

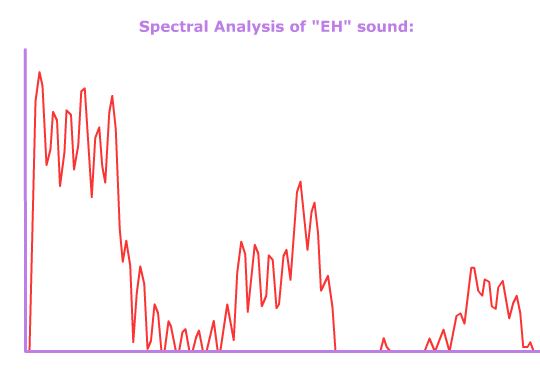

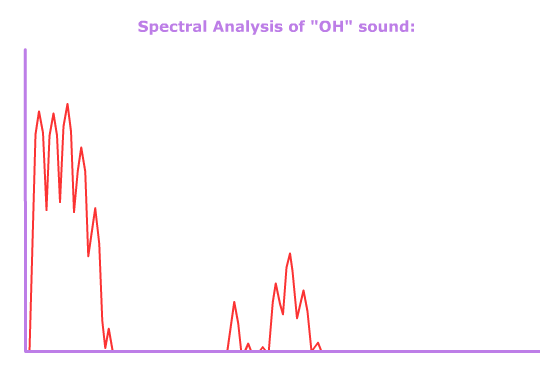

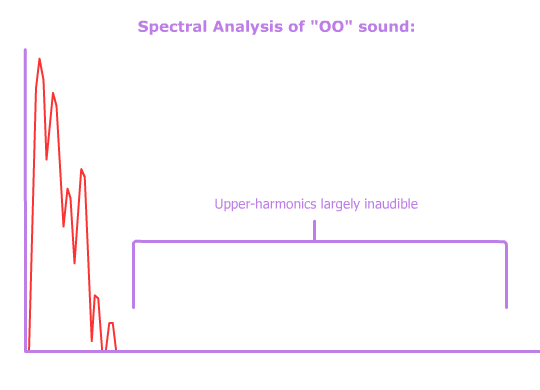

Our spoken language depends on the changing of Timbre in our voices:

Just by rapidly fluctuating the timbre of a single tone, we can produce the entire range of speech. The expressiveness of our spoken languages is proof of the extreme depth of Timbre. Upon listening to a sentence we interpret each separate Timbre as a building block of sound and fit these blocks together into a logical device of meaning. We do all of this instantly and without thinking.

Differences in Timbre are felt at a deeply instinctual level, but we often come up short trying to describe these exact differences. You can label the examples above as "the ah-sound, the oh-sound, the eh-sound, etc." but is this really adequate? Can we really describe the whole range of timbres by comparing them to those produced by the human voice? Why can't we meaningfully typologize Timbre like we've made a science out of doing with everything else?

Maybe our linguistic deficiency in the description of Timbre is because of the complications of timbral difference, or maybe our experience of Timbre is so instinctual that it can't be put into words. It might, however, be because the West never really considered Timbral differences important in the first place. In Western Theory, each note is not considered much more than a “pitch-class.” Harmonics are generally not considered in the way tones interact with each other. This might seem insignificant, but I think it’s actually at the crux of everything wrong with Western Music Theory. Timbre is the internal world of the Tone. To acknowledge timbre is to acknowledge the depth and importance of the Harmonic Series. To explore the possible timbral-expressions is to explore the internal organs of tonality; it the exploration of tonality at its most rudimentary.

One cool thing about how we hear the Tone is our capacity to hear Phantom Harmonics. The Overtones of a Tone are only INSTRUMENTAL towards the central pitch, so the removal of these harmonics will have timbral affects, but the Tone’s pitch will be preserved. What this tells us is that our ear KNOWS the general shape of the Harmonic Series and will “fill in the gaps” in order to comprehend it. This is, in itself, not super-interesting.When we see the front of an object, we instinctually imagine what it looks like from the opposite angle. All perception of the world around us requires some amount of imagination to fill in the gaps left by our senses. Basic stuff.

What is fascinating about the Tone is the sheer amount of missing information that can be filled in by our ears - how many "phantom harmonics" a Tone can be built upon while remaining consonant. We have probably been developing along-side the Tone for millions of years. Our ears have, over the course of our evolution, mastered the ability to hear the Tone in nature. Consequentially, we intuitively recognize the Tone, despite the absence of seemingly crucial harmonics.

What suprises a lot of people just learning about this is that even a tone’s TONIC can be removed and we will still hear the tone as that missing tonic’s pitch!

See? You still hear the pitch of this Tone as 100Hz, despite no such frequency existing! The serious implication of this phenomenon is that, when deciding the pitch of a Tone, our ear doesn't listen for the actual Tonic-frequency; rather, the ear examines the Harmonic Series and then identifies the implied Tonic of that series. If any group of frequencies fits into a Harmonic Series, we will contextualize them by imagining a Tonic!

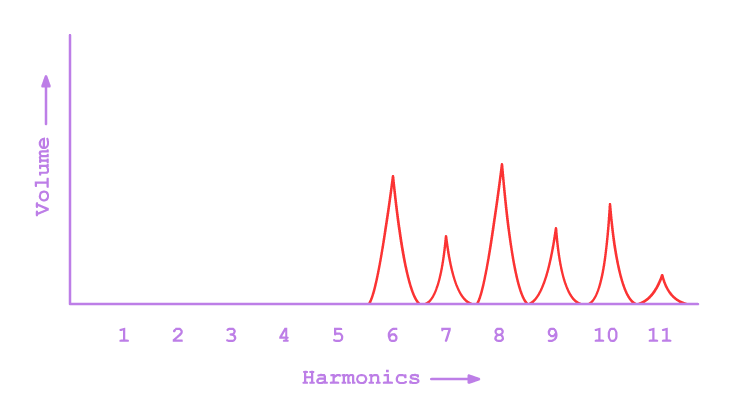

What if we go further though? What if we take away the first 5 HARMONICS of a Series?

The Tone definitely sounds emptier, but we still hear that tonic-pitch!

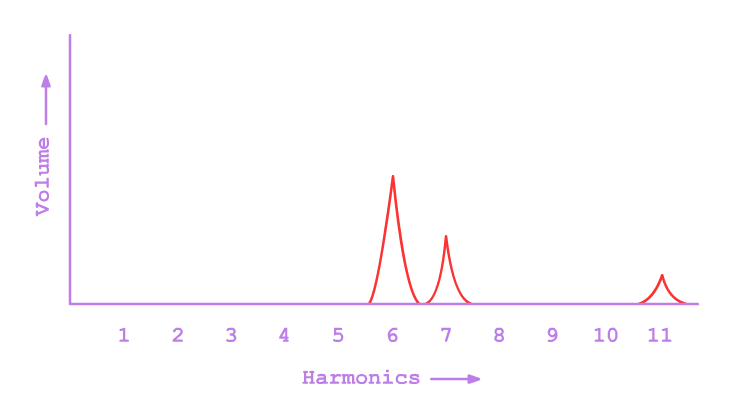

Okay, let’s go even further than that. What if we only play a few upper-harmonics? Let’s say 6, 7, and 11:

IT’S A TONE, albeit a very bizarre-sounding one. Do you see how far the ear is willing to stretch its imagination to perceive Tonality?

The ear obsessively investigates for tonality. It will go to great lengths to make sense of the frequencies around it. Every group of frequencies even remotely implying a Harmonic Series will be dragged into the light and branded a “tone.” Our ear's tendency to imagine a tonic in order to justify a group of frequencies as tonal should illustrate just how deeply the Tone is ingrained into our subconscious.

The Tone, by acting as a sanctuary of sound in the midst of noise, opens up the possibilities of the Harmonic Universe. The Tone is the embodiment of Consonance, so all of its the inherent qualities - its unifying magic, its hierarchical strucure, its tonic-to-overtone relationship, its capacity for phantom-harmonia, its timbral expressions - expand to the qualities of all Consonant harmony. Any Consonant Harmony is really just a macrocosmic representation of the Tone, achieving its Consonance only by imitating tonal qualities. All Consonance is simply Tonal resemblance, and the entire game of Harmony has been finding as many ways to "resemble" the Tone as possible.

That the basis of Consonance is something as complicated as "resemblance" and not something as autistic as "simple ratio," explains the extreme difficulty Music Theorists have in quanitfying Consonance. If Consonance was purely numerical, than we would have, at some point in the last 2500 years, discovered some algorhythm through which we can input a midi file and get some kind of rigid consonance-map. The fact that no one has even come close to creating such a thing testifies to the weakness of any numerical basis for consonance.

The reason it is so difficult to quantify Consonance - to look at two chords in a song, for instance, and explain why one chord is more consonant than another - is that we are trying to quantify RESEMBLANCE. There are so many different ways for sound to "resemble" a Tone, that any quantitative measurement of tonal resemblance will be, at the very least, extremely multivariable. The Consonance-to-Dissonance polarity does not belong on a single axis; there are too many moving parts. It is better to avoid any quantitative description of Consonance in the first place. Something as inseparable from the human-experience deserves to be talked about in HUMAN terms.

If the Tone represents warmth and familiarity, then any Tonal imitation reflects and, consequentially, distorts this familiarity. How many ways can we transform this pure gem of Consonance while keeping it intact? How many ways are there to stretch and compress and multiply and split apart the Tone? How roughly can we play with the PUREST CONSONANCE before it breaks and our illusion of any kind of Consonance is completely shattered? These are the questions that the "progressives" throughout the history of Western Music were unconsciously trying to answer. They are the problems that every young composer challenged himself with when he reached out farther into the void of dissonance. That Tonal "resemblance" can be interpreted in so many different ways is both a nightmare for the dogmatic theorist and a blessing for the musician.